How personal can a critic’s voice be? Where is there room for the scholar’s “I” - not the rhetorical one, but the real one?

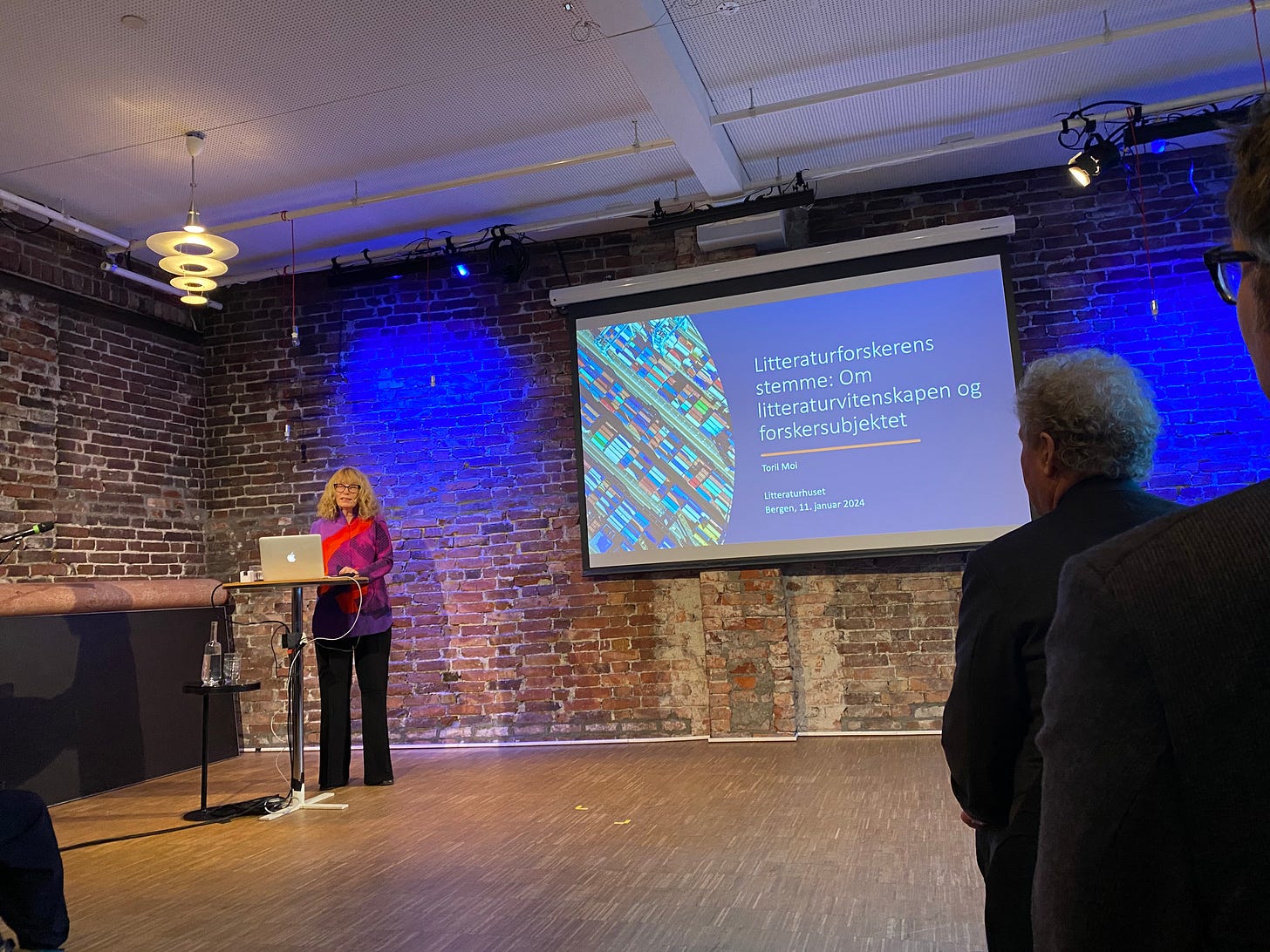

On 11 January I attended a seminar honoring the 70th birthday of literary critic and scholar Toril Moi, who was educated at the University of Bergen (where I now work) and has been teaching at Duke University for many years. She gave a wonderful lecture (in Norwegian) on what it means to have a voice as a literary critic and a literature scholar – and what even is a critic or a scholar? Towards the end she discussed the criticism she received for writing herself and her reaction to a piece of literature, into a piece of criticism: that is was too private, not scholarly enough, wholly inappropriate. Moi challenged this expectation that we must not allow our own subjectivity into criticism. Her final slide:

Can reading do something to the critic?

A text is not a passive object

A text makes demands of the reader

A critic can end up not being worthy of the text

Texts are historically anchored expression and action

To read is to meet the other

These points generate so many thoughts and open up so many interesting questions. For me I immediately began to think about my trade book project (described in the previous newsletter post), a book that develops a new relationship between myself as critic, the historical texts, the historical subject, and my readers.

In one view Visionary: The Woman Who Changed Medieval England is an academic book: it is anchored in historical research, in archival discoveries, in scholarship and in some of the rhetorical moves we make as academics. In another way it is not academic; rather, it is non-fiction: maybe even creative non-fiction. I weave myself, my experiences, my life into the text, to a certain, limited extent. It’s not autobiographical per se but I present research subjects through my own experiences visiting their locations and feeling their texts. This new genre (for me) gives an exciting, risky freedom. I can bring forward my own thoughts in a way that’s not really permitted — or not typical at least — in purely academic writing. It’s not autobiographical, or confessional, in this case, but there’s more of me in the book than usual. How will that go? What is the risk? What can be gained?

Scholarship has a presumption of objective criticism and interpretation of the subject (text or history, etc). But this is a false premise. We who write are always in our text: the words come through our brain, they are ours, there is nothing objective about them because they are created in and through our subjectivity. To talk about ourselves and our relationship to our subjects is only to admit the truth, to be honest about what applies to all authors but only some dare to admit. It’s easier to look at other subjects than to look at ourselves in the mirror as a subject and perhaps be critical against ourself at the same time that we criticize other subjects whose feelings we don’t feel, or who are long gone and no longer feeling.

I’m drawn to this honesty because it feels so refreshing.

Drop the scholarly tempests-in-a-teapot, drop most of the footnotes and as much posturing as possible, instead talk as a human telling a story to other humans around the fire. It feels instinctual and right. Not that it’s easy — I have been indoctrinated in a different voice all these years, and of course my scholarly voice is right there, fading in and out, there with ‘facts’ etc. But in bringing back in the ‘I’ in a more honest way, not just as a rhetorical positioning tool, I’m being honest about the mediation that’s always there between my readers and my subject. Authors are always a veil, shading and interpreting, what we ‘reveal’ — through a glass darkly. To describe that veil, and admit the feelings woven into it, puts you on the same side as the reader, both of you looking at the book and its author together, like Dorothy and her gang now standing next to the Wizard of Oz all on the same side of the curtain.

Birgitta and her editors certainly thought about these issues. Birgitta (and all visionaries) see themselves as channels for these messages from God, but the divine cannot even be directly understood by the human mind, much less processed by our mortal language and communicated effectively to others. The divine must be mediated by our own humanity and our own words. The incalculable scale of that mediation between God’s Word and human words is perhaps the most profound of any mediation that occurs. At the same time, the visionary has to convince us that they are effectively presenting a truth that is very very very close to what they experienced, a truth that is reliable. Is the best way to convince us to front their own subjectivity or to ignore it? The answer varies from person to person, page to page, moment to moment.

Both 700 years ago and today these tensions between the author’s voice and subjectivity and objectivity are gendered. Who is allowed to have a voice that reflects on itself and elevates itself to the level of subject? Who is allowed to talk about themselves? What genres invite in the author’s private self — when is it dismissed as navel-gazing, when is it elevated as profound? I suspect the critical reaction to Moi’s personal voice seeping into public criticism was partly based on the bias that women are too emotional, and thus unreliable as critics. This bias has been seen in fiction/autobiography: one of the most successful books (or series of books) recently has been the enormous My Struggle of Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard, an extremely detailed narrative of his everyday and inner life. Some people have said that style would never fly if written by a woman: the book would be panned and no one would take it seriously (that surely happens all the time already). This reminds me of a quote I cite in the introduction to Visionary, from an excellent Lithub article by novelist Siri Hustvedt, where she describes her interview of Knausgaard:

Near the end of our talk, I asked him why in a book that contained hundreds of references to writers, only a single woman was mentioned: Julia Kristeva. Were there no works by women that had had any influence on him as a writer? Was there a reason for this rather startling omission? Why didn’t he refer to any other women writers?

His answer came swiftly, “No competition.”

I was a little taken aback by his response and, although I should have asked him to elaborate, we were running out of time, and I didn’t get a chance to do it. And yet, his answer has played in my head like a recurring melody. “No competition.” I don’t believe that Knausgaard actually thinks Kristeva is the only woman, living or dead, capable of writing or thinking well. This would be preposterous. My guess instead is that for him competition, literary and otherwise, means pitting himself against other men. Women, however brilliant, simply don’t count…

Why is this? I think part of it relates to my point here, that women almost always lose when it comes to writing their personal subjectivity into a text, because the standard for subjectivity is male, and has been for thousands of years.

That’s why I feel compelled to write this book, and to do all the research I do: to validate women as subjects, to unearth forgotten stories of women in history, changing the world, making beautiful, brilliant things.

Something about these medieval women’s texts invites us (me) in to be subjects alongside them, just like Dorothy and the wizard on the same side. This feeling I have is partly gendered — that is, dependent on my gender as woman, their identification as women, and the fact we share that gender across time and space. But I think Birgitta can appeal to any human regardless of gender, creed, age, or background knowledge. Each will have their own individual relation to this unusual women from the distant past. What I try to do in this book is capture my own feeling of being invited into Birgitta’s world through her book, her words, her voice, in the same way that so many medieval people felt invited in—some of these are the medieval English readers I present in each chapter. I invite in my readers to that ‘fellesskap’ — fellowship — with those historical readers, all reading the same visionary author. Maybe some would disagree with that attempt. Maybe it is too personal of a relation to this women, to these readers, too informal. But I would say it does not discount or devalue the literary/historical subject to come closer to them personally: in contrast it grants them a more humane, nuanced respect than allowed by the often flat, sterile position of ‘merely’ academic subject.